New Topographics: photographs that find beauty in the banal

With its stark yet oddly romantic images of American factories, intersections and trailer parks, William Jenkins's 1975 exhibition rewrote the rules of landscape photography. Does it have the same impact today?

Mundane yet mesmeric ... Stephen Shore's photograph of an alley in Presidio, Texas (1975)

It is 35 years since the term "new topographics" was coined by William Jenkins, curator of a group show of American landscape photography held at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. The show consisted of 168 rigorously formal, black-and-white prints of streets, warehouses, city centres, industrial sites and suburban houses. Taken collectively, they seemed to posit an aesthetic of the banal.

"What I remember most clearly was that nobody liked it," Frank Gohlke, one of the participating photographers told the LA Times when the exhibition was restaged last year at the LA County Museum of Art. "I think it wouldn't be too strong to say that it was a vigorously hated show."

The exhibition's clunky subtitle was "Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape", which gave some clue as to the deeper unifying theme. What Jenkins had identified in the work of US photographers such as Gohlke, Robert Adams, Stephen Shore, Lewis Baltz and Nicholas Nixon was an interest in the created landscapes of 70s urban America. Their stark, beautifully printed images of this mundane but oddly fascinating topography was both a reflection of the increasingly suburbanised world around them, and a reaction to the tyranny of idealised landscape photography that elevated the natural and the elemental. In one way, they were photographing against the tradition of nature photography that the likes of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston had created.

Adams, who is now perhaps the most well-known chronicler of America's disappearing wildernesses, pointed his camera at eerily empty streets, pristine trailer parks, rows of standardised tract houses, the steady creep of suburban development in all its regulated uniformity. Baltz made stark photographs of the walls of office buildings and warehouses on industrial sites in Orange County. Nixon concentrated on innercity development: skyscrapers that dwarfed period buildings, freeways, gridded streets and the palpable unreality of certain American cities in which pedestrians seem like interlopers.

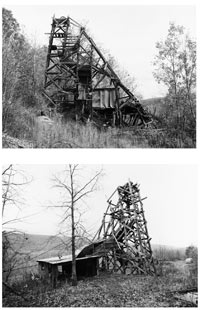

Coolly architectural ... a detail of Hilla Becher's series of Pennsylvania pit head photographs (1974)

Coolly architectural ... a detail of Hilla Becher's series of Pennsylvania pit head photographs (1974) Jenkins also included American work by Bernd and Hilla Becher in the show. The Bechers' stark images of Pennsylvania salt mines and giant coal breakers were as coolly architectural as their images of German cooling towers and industrial plants. The suggestion was that there was something determinedly European about this new American gaze.

Only one photographer, Shore, shot in colour. It seemed to heighten the sense of detachment in his photographs of anonymous intersections and streets. Shore was influenced by Ed Ruscha, the conceptualist of Californian cool, who, in the 60s, had made a series of artist's books with self-explanatory titles such as Twentysix Gasoline Stations, Some Los Angeles Apartments, Every Building on the Sunset Strip. The show also nodded obliquely at the later work of Walker Evans, who had photographed the vernacular iconography of America in road signs, billboards, motels and shop fronts.

Evans's images now carry the romantic undertow of an almost vanished America. The work of the photographers in the New Topographics exhibition, now collected in an austerely beautiful book of the same name by Steidl, still looks, for the most part, contemporary – and still seems troubling in its matter-of-factness, its almost dull reflection of the uniform and banal. A friend of mine who works in publishing dismissed the book outright, saying: "If I were to commission a bunch of authors to write essays on boredom, I would not expect the result to be a bunch of boring essays. Nor would I give it a pretentious postmodern title." Outside the rarefied world of art photography, many would, I suspect, agree.

The influence of the New Topographics movement, however, has been pervasive. You can detect it in the work of Andreas Gursky, Paul Graham and Candida Höfer. Indeed, Donovan Wylie's clinical approach to photographing the empty Maze prison in Northern Ireland, currently shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse prize, could easily have been a contemporary addendum to the Steidl book.

The New Topograhics exhibition in 1975 was not just the moment when the apparently banal became accepted as a legitimate photographic subject, but when a certain strand of theoretically driven photography began to permeate the wider contemporary art world. Looking back, one can see how these images of the "man-altered landscape" carried a political message and reflected, unconsciously or otherwise, the growing unease about how the natural landscape was being eroded by industrial development and the spread of cities.

Back then, Jenkins seemed to have anticipated what the public reaction to the show would be. University students were on hand at George Eastman House to interview visitors for their reactions, most of which were negative or dismissive. One man was surprised to find his own truck in one of Adams's photographs, and had this to say: "At first they're really stark nothing, but then you really look at them and it's just the way things are. This is interesting, it really is."

No comments:

Post a Comment